Corsica – island

Napoleon claimed that he could recognize his home by its scent. And indeed, Corsica smells so intense like no other Mediterranean island. The perfume of the island of Corsica is called macchia, an impenetrable plant carpet of juniper, broom, myrtle, mastic, thyme, lavender and many other herbs and shrubs.

Corsica in the spring is a little paradise for smelling people, hell for pollen allergy sufferers. Macchia used to be the name of the Corsican resistance because politically persecuted or common criminals often hid in the Corsican jungle of plants. Today, macchia has become a trademark for the various products, from the liqueur to the bath oil to the perfume. An advertising slogan that promises sales.

In the summer, the maquis is a problem. The dense undergrowth dries quickly in the heat and burns like tinder. A carelessly thrown away cigarette or a piece of broken glass, in which the sunlight is bundled, are enough to cause disastrous fires. Often the fires are laid, here by farmers, to clear the fire, there by landowners who want to create so new building land. Quite the backgrounds are rarely clarified. Corsica holds a sad record. Because nowhere in Europe does it burn as often as it does here, about 500 times a year. 30 firefighting planes are stationed in Corsica. They are on alert around the clock.

Severe forest fires in 2003 left 18 people injured in Corsica. On a weekend alone, in the Haute Corse department, 7,100 hectares of forest and shrubs burned down. 650 firefighters were on duty.

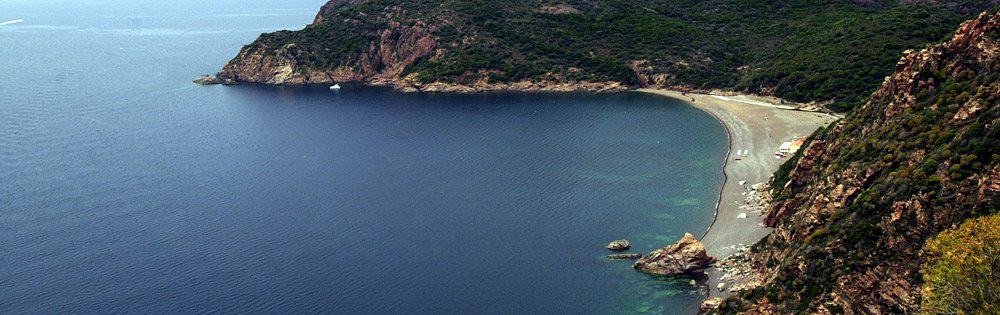

While the east coast is lined with long sandy beaches, the west coast offers partly rocky, partly sandy smaller and larger bays. If you are looking for Ibiza excitement and cultural highlights, you will be disappointed. Corsica is known for its landscape of clear streams and rivers whose waters you can drink uncooked. While there is still snow in the mountains, the Mediterranean often lures with 20 degrees Celsius of warm water.

Here are alpine landscapes and secluded bays so close to each other, nowhere else. With a mean altitude of 568 meters, Corsica is considered the most mountainous island in the Mediterranean. More than half of the island is over 400 meters, 50 peaks are higher than 2,000 meters. The highest mountain, Monte Cinto, measures 2,706 meters. And the feeling of altitude is particularly intense because the sea is so close.

If you walk through Corsica or sit on one of the many small wild beaches, you get a feeling of what the Mediterranean might have been like a thousand years ago. They still exist, the places where you can only hear the wind and the birds, or the constant murmur of the sea on the coast. In summer it is then in many places in Corsica with the rest over.

Then an armada of stinking motor yachts and jetski roars along the coast. On many backs of automobiles and motorcycles you can see him as a sticker, the black man’s head with frizzy hair and white headband, the freedom symbol of the Corsairs. The experts come to no clear statement, where the Corsican symbol comes from. In 1762, the head of a moor with a headband under Pascal Paoli became the official coat of arms and symbol of the freedom struggle of the Corsicans.

There are many stories about the origin of the Mohrenkopf as a symbol of the Corsican national feeling. Historians say the origin is in Aragon. During the period of power struggle between Pisa and Genoa, the Pope appointed the King of Aragon as administrator for Corsica and Sardinia.

Aragon’s flag already showed four Moors, scattered around a cross, which probably stems from the victories over the Arabs during the Crusades. Vincentellu d’Istria, a cook in Aragon’s service and builder of the Citadel in Corte, fought against the Pisan and Genoese occupiers. He probably brought the korsen the moor head.

He was viceroy in Corsica, but was soon defeated by the occupiers and executed in Genoa. Corsican music is often about suffering and death. Many Corsican groups have rediscovered the old songs and rearranged them with modern rhythms and instruments.

Sung almost always in Corsican.

language Corsican is a language of the Italian-Romance group. As simple as that sounds, linguists have done so hard to acknowledge it.

For only with the publication of the scientific lexicon of Romance linguistics in 1988 was Corsican included in a list of 14 Romance languages and ennobled linguistically. Corsican is not an imported or modified Italian, but the result of a long language development from the ancient Latin. The Tuscan influence was very strong in the 9th century.

The Genoese left behind, despite their five centuries Political rule only a little of their language, since they too Tuscan took over as a written language. The Corsicans are committed to the recognition of their own language. This is most evident to the visitor when he sees the overspent place signs, for example Morosaglia in Merusaglia or Corte in Corti.

The Corsican place names are predominantly Italian, because Genoa put on sale to France in 1769 a condition: that the place names should remain Italian. In small steps, the recognition of the language is gradually gaining ground. The local associations are left to decide whether they want to set up new place signs with the old names. Porto is called Portu again today. Corsican can be studied in Corte and is now officially recognized by the French government as a regional language.

Thus, it may be taught in schools, but still does not have the status of a compulsory subject, which many Corsicans demand.

Hiking Corsica’s high alpine world is not for beginners. Part of the walking routes is very demanding and requires good physical condition and plenty of climbing experience. About 30,000 hikers visit the island every year. The GR (“Sentier de Grande Randonèe”) 20 is probably the best known European hiking trail. It runs along the main watershed of Calenzana in the northwest of the island at Calvi to Conca in the southeast, near Porto Vecchio.

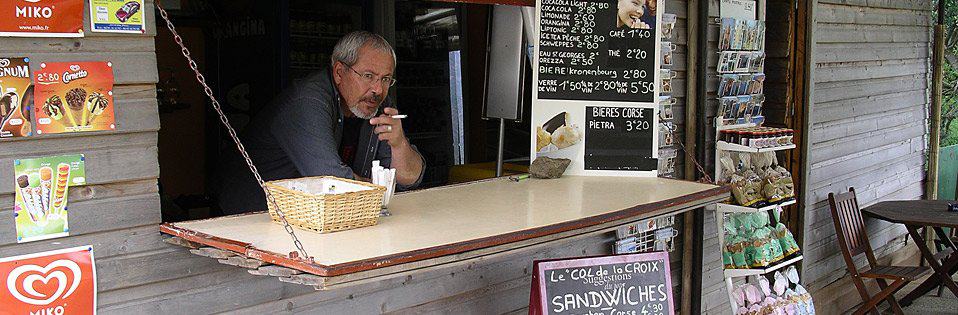

The track measures about 170 kilometers and 10,000 meters in altitude. The GR 20 leads largely through wild, uninhabited area and touches as the only place Vizzavona. Overall, the GR 20 meets only four times on a road, namely the most important passes: Col de Vergio, Col de Vizzavona, Col de Verde and Col de Bavella. The route can be completed in 12 to 15 stages. 13 huts offer the hiker protection. In a narrowly marked part may also be camped near the hut.

As an alternative to the GR 20, there have been easier routes between five and 20 hiking days for some years, for example Mare e Monti, Mare a Mare Nord, Mare a Mare Sud.